|

|

Introduction

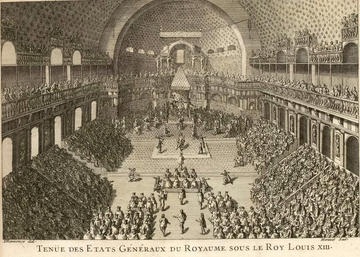

The year 1616 found France witness to a period of deep societal stress and a general malaise felt throughout

much of the kingdom. Threats of uprisings from the Prince of Conde and other malcontents, the preeminence of the Roman Catholic Church, the minority rights of Protestants, an unfair tax system, and the marriage of the young French king to a Spanish princess were among the most pressing issues of the day.

The Estates

General, a once-in-a-generation body politic wherein much hope had been placed, had ended the previous year in utter failure.

This was the result of the unwillingness of the three estates to come together on any meaningful recommendations on the critical questions before them, and the crown having its own motives, which in the short term was looking to secure the continuation of the Queen-Mother as regent on behalf of her juvenile son, and in the long term

was looking to institute a more centralized, authoritative government under its control.

Responding to the deplorable state of his nation, a book of no literary acclaim was caused to be printed by an anonymous author titled

Histoire du Grand et Admirable Royaume d'Antangil...

Since having been reintroduced to the world in 1922 by famed French bibliophile, Frederic Lachevre,[1] who dubbed it

"the first French Utopia", the mystery surrounding the identity of the book's anonymous author has remained its near-sole attraction.[2]

Yet inside these Moroccan-leather covers, cloaked in the guise of a historical adventure,

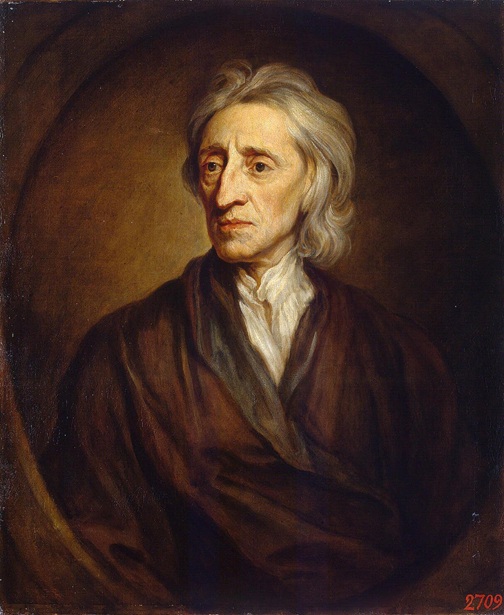

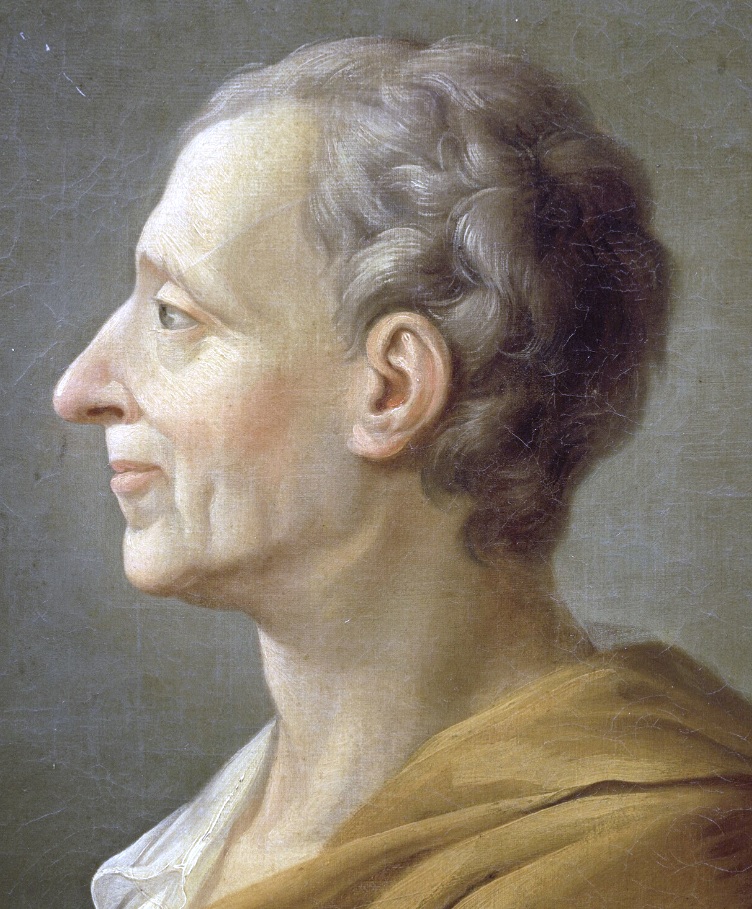

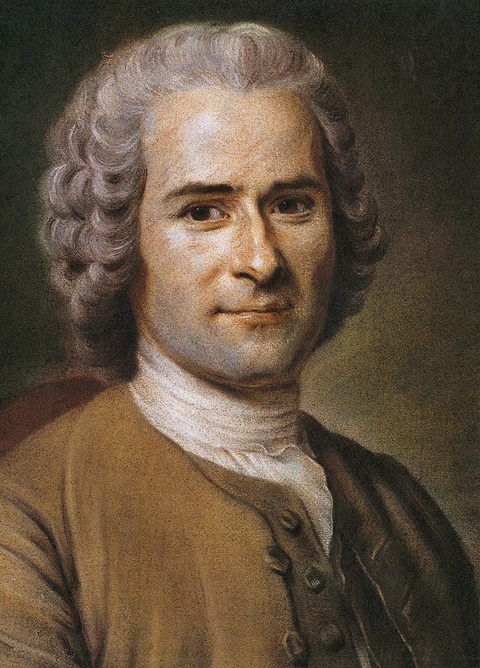

a political treatise of great merit awaits. For bound within are expressed guiding precepts and fundamental principles found in the later writings of

Locke, Montesquieu,

Harrington,

and Rousseau, among others. Ideas that 170 years later

would be

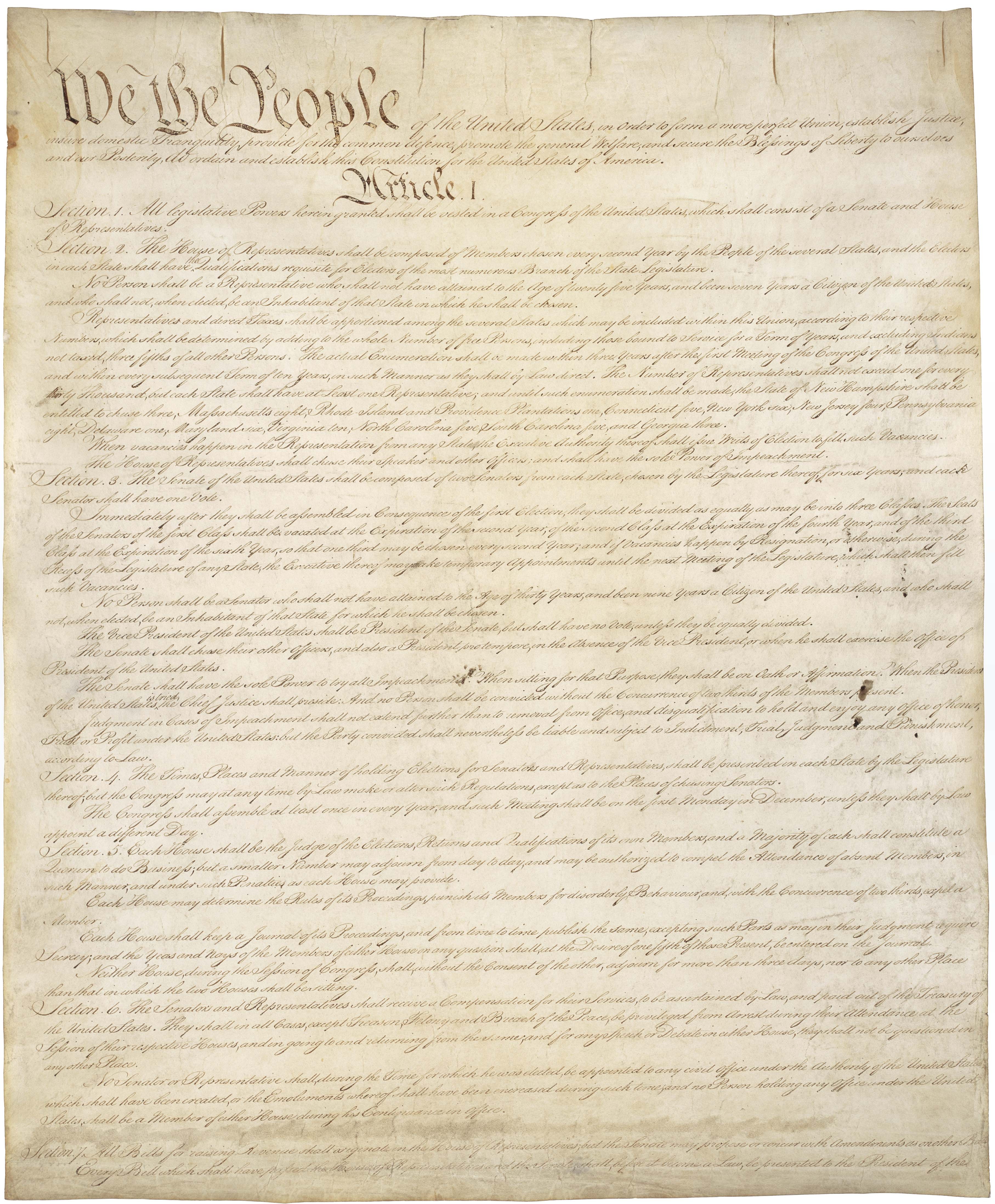

enshrined in our own American Constitution and implemented by our founding fathers. Such novel ideas as an elected sovereign, with limited powers, who could be removed at any time for bad behavior; term limits for elected officials; an

independent judiciary; a bicameral legislature; federalism whereby laws enacted by the Senate would be returned to the local provinces & there could be accepted or rejected in full, or could be altered to suit each of the local populations.

Some of the same ideas and principles found in Antangil would facilitate a fledgling American republic to rise out of the ashes of revolution,

to soar to heights unbound, unto a grace yet to be achieved.

Yet with all that said, it's ironic in the least that nearly all those who have commented on this book have given it a poor review, some have even termed Antangil a dystopia.

But all these negative reviews have been looking at the book from mainly a literary perspective. An exception to this was

Gilbert Chinard,

a French-born American historian and Jefferson scholar, who recognized the similarity between Antangil and the U.S. Constitution. Chinard writes of the

book's

unknown author:

| |